3,725 Health Posts Mapped in Jakarta in a Massive Grassroots Empowerment Effort

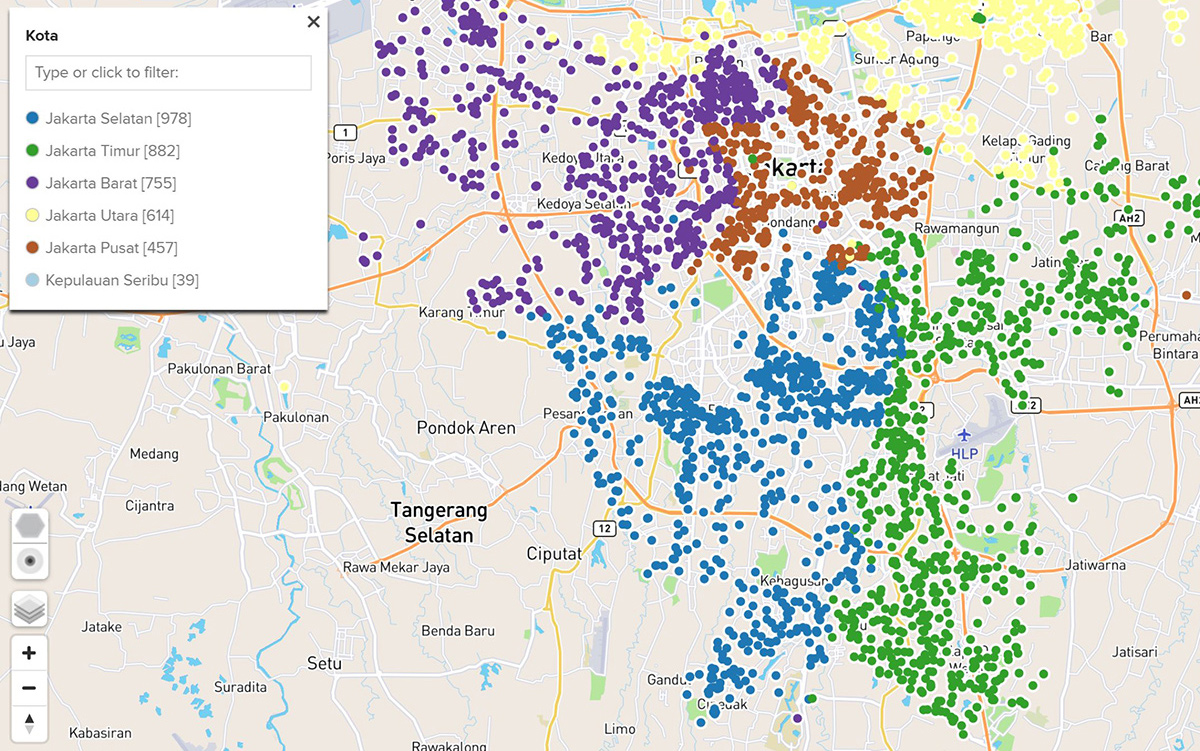

Health posts in Jakarta mapped by PKK.

Health posts in Jakarta mapped by PKK.

We caught up with Renold Lim, a volunteer at Jakarta-based grassroots organization Pemberdayaan Kesejahteraan Keluarga (PKK), which aims to improve health services to the urban poor by sharing data about the realities of street-level health services. It is a colossal effort. Given that the city of 10 million has 400,000 poor residents, it requires coordinating and training over 1,200 volunteer data collectors to map data from 3,725 health facilities. They’ve managed to do this successfully — so far their efforts have resulted in more funding, new equipment, and government buy-in. In this short interview, Renold shares some tips for making the process go smoothly and what works at scale.

ONA: Please tell us about your organization and what you’re trying to do

RENOLD LIM: PKK is a non-governmental, non-profit organization based in Jakarta. Our mission is empowerment for family welfare and we have existed for over 45 years. Our activities include organizing pre-school education for the poor, running vocational classes for women, and advocating for public spaces in low-income areas. An ex-government official runs it. I got involved in March 2016. I was a volunteer at the Office of the [Jakarta] Governor and was introduced to the governor’s wife, who is involved with PKK.

Health workers and families at a posyandu.

Health workers and families at a posyandu.

PKK has projects that require proper planning to ensure positive impact. However, they were using a manual, paper-based process to collect data. This data was not actionable. So I got involved to transition their activities to a digital process using Ona. One of the first projects for me is this one about posyandu (health care posts) — we have more than 4,600 posyandu all over Jakarta, and we don’t have any information regarding the locations and status.

What have you done so far?

When I started, PKK already had a large, established volunteer workforce — some of who were not comfortable with technology. I had to figure out a way to train everyone on the new mobile-based tools. In June 2016 we started by training a small, influential group on Ona. This included the technical team, one municipality out of the six in Jakarta, and the secretary of PKK in Jakarta. We [came to a shared understanding of our goals], then created a simple PowerPoint and a training form, which was a duplicate of the real form we planned to use. Over the next 5 months, we trained over 1,000 data collectors. One-on-one training helped address issues early instead of responding during live data collection.

Do you have any tips to share about what you’ve learned?

It’s important to be very careful composing forms. Discuss and brainstorm with leadership because there’s a “no turning back” point when doing big projects like this. We learned that the hard way — we ended up having to throw out a lot of data in the beginning.

Volunteers provide food to ensure kids get a proper meal. This also serves as a teaching moment to mothers.

Volunteers provide food to ensure kids get a proper meal. This also serves as a teaching moment to mothers.

Another thing is to make the form as easy as possible. With so many data collectors, it means some of the users won’t be as knowledgeable, but you have to make sure the data is still collected correctly. Relatedly, enumerators need to understand and be bought into the goals and spirit of the project.

Also, we didn’t plan to start collecting data until January 2017, but as soon as workers were done training around October 2016, they were so excited they just started collecting data. We ended up finishing early. The lesson here is to use momentum when it comes up. We learned that technology can really make people feel empowered and connected.

How are you using Ona tools?

We collect data using Enketo webforms. We found it very useful because we just had to share a URL with the field agents. The collected data is about posyandu and includes GPS location, leader name, tools they use, conditions of the health post, and photographs. Besides data collectors, we have 50 volunteers from the municipal council of Jakarta and the Government. These volunteers are M&E specialists who use Ona dashboards to make sure data is accurate and flag errors for correction.

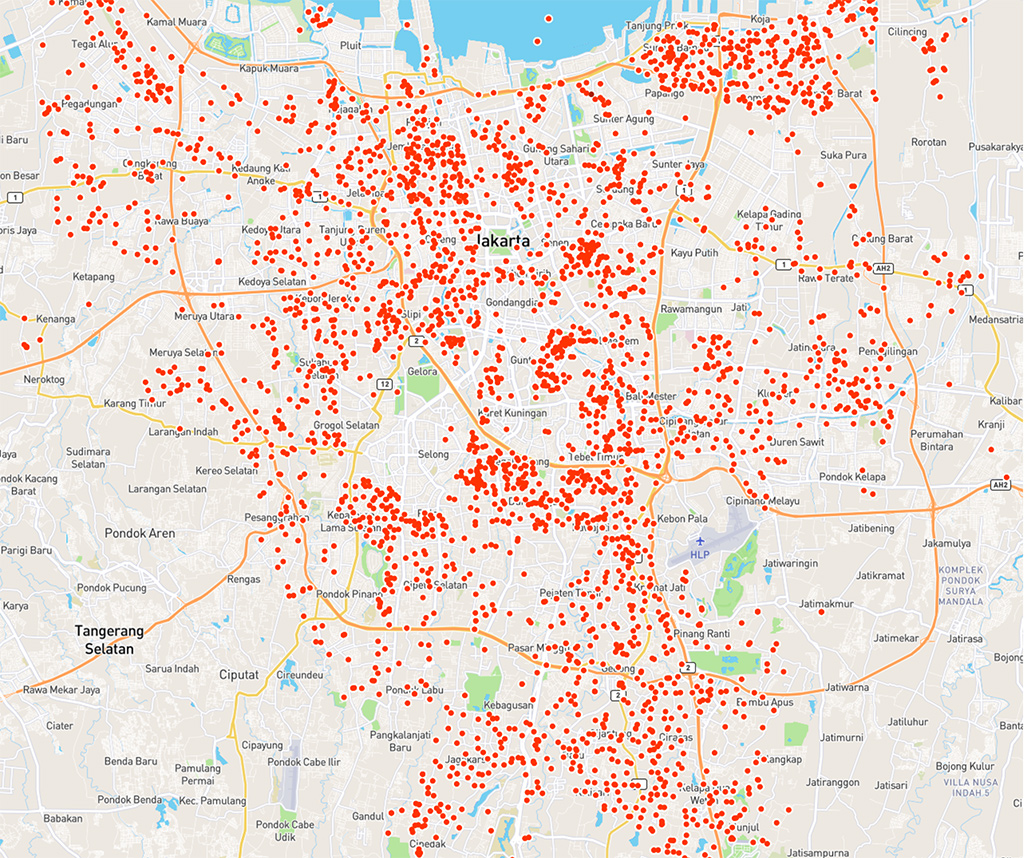

A map of 3,725 posyandu in Jakarta.

A map of 3,725 posyandu in Jakarta.

We use filtered datasets to view only a portion of the data and to download only the data we want, and not everything. One thing I love the most is the map view. We can view the whole city of Jakarta at a glance, and the ability to use colour codes for GPS points to differentiate data is amazing. We use it to colour-code municipalities. Looking through photos and searching on tables are also very useful to cut through clutter. One thing we realized was that people find Ona very easy to use. With minimal training, people were able to use Enketo and view dashboards.

We also sync data to Google Sheets, where we use Awesome Table, an automatic dashboard maker that makes it easier for us to get insights and the data is always up to date.

What kind of reaction has there been?

The government is very active in asking for data. They like to know about our progress and how many health posts we have data on. We present information based on their questions, and so far they are really impressed by what we’ve been able to do in a short time. It’s been much easier getting data into an actionable format, especially with accurate data and locations. We’ve registered 23,000+ health care workers from 3,725 health care posts. It’s still early, but so far the government has responded with new equipment and funding for health posts.

An indoor education session.

An indoor education session.

A new baby scale brought by the government after field observation.

A new baby scale brought by the government after field observation.

Sounds like your project has gone well so far. Good luck with your next steps!

Thank you!

Pemberdayaan Kesejahteraan Keluarga and Renold Lim are recipients of an Ona Impact Grant for their posyandu-mapping project in Jakarta. If you are interested in using Ona with your projects, check out our plans.