The Perfect Kenyan Chapo

The Ona team convenes at Dickson’s home to learn the art of making chapo. Recipe and photos below.

The Golden Ticket

Since my first lunch in Nairobi, Dickson has insisted that all restaurant chapatis pale in comparison to his mother’s recipe. Here’s how every lunch would go when I’m in town:

“This is great!” I’d say, devouring a chapati.

“Not really,” he’d respond, ordering rice.

So a few weeks ago, when Dickson invited Peter and I to his house to try good chapo, we jumped at the chance. On a typical pleasant Nairobi Saturday, Moses (Dickson’s neighbor), Peter and myself joined Dickson and his sister Annette at their home. We took a taxi to west of Nairobi and when we arrived we learned something miraculous: we wouldn’t just be trying the greatest chapo in the world — we’d be making it from scratch.

Only as Good as the Ingredients

“Where’s the chapati flour?!” Dickson asked.

“You’re holding it!” Annette said.

“This is all purpose! It’s not right!” Dickson said.

It turns out good chapati can only be made with EXE® Chapati Flour. Before we even started cooking, we had to go hunting for the right flour. We walked to a nearby corner store: out of stock. Another one: nope. Finally, a market further down, past two vegetable stalls and through a muddy alley, had it in stock. The day was saved.

Dickson and Peter, with EXE flour.

Who Runs the Show?

It was immediately clear that Dickson was out of practice making Chapo. He started trickling water into a large bowl of flour.

“It’ll take an hour to mix in the water at that rate!” Annette said, pouring most of warm water all at once. While Dickson was adamant about ingredients, Annette ran the show. She did not need a recipe, combining seemingly random amounts of ingredients together, feeling the dough to test it, and ordering us to do the grunt work of kneading and rolling — admonishing us when we failed to meet her standards. Uneven chapati were discarded, efficiency was demanded, tears flowed.

The Right Way to Roll

Moses watched us role a few batches of chapati before he introduced Mama Moses’ way of rolling chapati. He questioned the wasted effort in Annette and Dickson’s double-roll method, selling Peter and I on the virtues of his single-roll method. The hosts dismissed it: their house, their rules.

Looking back, I don’t think Annette and Dickson followed the recipe so strictly because of inherently uncompromising personalities. Instead, it was because the receipt wasn’t theirs — is was their mother’s. This recipe was passed down and although it’s simple, any variation means it isn’t right because it embodies their home and family.

Mama Dickson’s Chapo Recipe:

Although sharing a name with Indian chapati, chapo is actually more similar to Indian paratha, using only all-purpose flour and having more oil than Indian chapati. It is savory, layered, and a delicious and perfect accompaniment to any stew.

While Dickson insists EXE® is the best chapati flour, any all-purpose flour will do. I’ve also made this at home a few times with 1 part all-purpose to 3 parts whole wheat flour with no adverse effects.

Serves: 4–6 (1–2 chapo’s each)

Time: 1.5 hours, 6 hours if you are taking breaks to talk with friends.

Ingredients

- 2 cups warm water (38°C)

- 1 tsp salt

- 4 cups all purpose flour

- Neutral oil (corn or canola)

Equipment

- Rolling pin

- Place to roll dough into circles

- Wide pan (preferably cast iron)

- Optional: Kitchenaid Mixer

Instructions

Mix it. Dissolve the salt into the water. Pour just enough water into the flour to make an elastic dough that’s slightly sticky. How much water you’ll need depends on humidity, elevation and how the stars are aligned. Roll the dough for 10 minutes. Stick your fingers in the top and put about 1 TB of oil into the holes and knead to incorporate. Cover the dough and let it rest for 20 minutes.

Roll twice. This is where it gets complicated. Flour up a flat surface and grab half the dough. Roll flat it into a circle about 0.5 inches thick. Brush oil on the top. Cut out a slice, roll it up, and then roll it out into a tube. Then, curl this tube around your finger until it’s a thick patty. Squash it and roll it into a circle, this time about 1/8” to 1/4” thick. Ideally it’s a circle, but the most important thing is consistent thickness. Make sure it fits your pan. You should not roll out too many ahead of time since the dough will develop dry skin. Get a partner to help roll as you cook. In our case, it took 3 men to keep up with Annette’s cooking. In case you are wondering, rolling twice is meant to produce layers. It is said “a well made chapo can be read like a book” because of it’s numerous layers.

Cook then scorch. The chapo needs to be cooked twice. Preheat the pan to medium-high heat for a few minutes. Place a round of dough in the dry pan without oil. When the bottom gets a few light brown spots, turn it over. While the second side is cooking, brush the top with oil. Turn the chapo back over to “scorch” the first side. When you get a few large brown spots on the first side, oil the second side and scorch it. You can gently squash bubbles that come up for even cooking.

Enjoy with stew, sukuma, or beans, or with cinnamon sugar and tea the next morning.

Chapo Visualized

Dickson and Peter making dough.

Rolling the dough out into a big circle.

Adding a layer of oil.

Cutting a rolled wedge out of the big oiled dough circle.

Rolling the rolled wedge into a dough snake.

Wrapping the dough snake into a bun, then tucking the end up-over and through the middle.

Rolling buns out again into circles.

Annette examining the weight and evenness before cooking.

Cooking each side dry (without oil) first, then brushing with oil, then scorching each side.

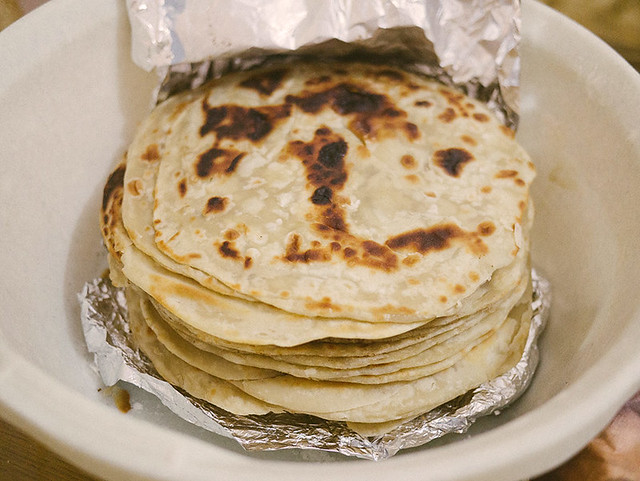

Stacking ‘em up!

Enjoying with pea stew, sukuma wiki and cabbage.